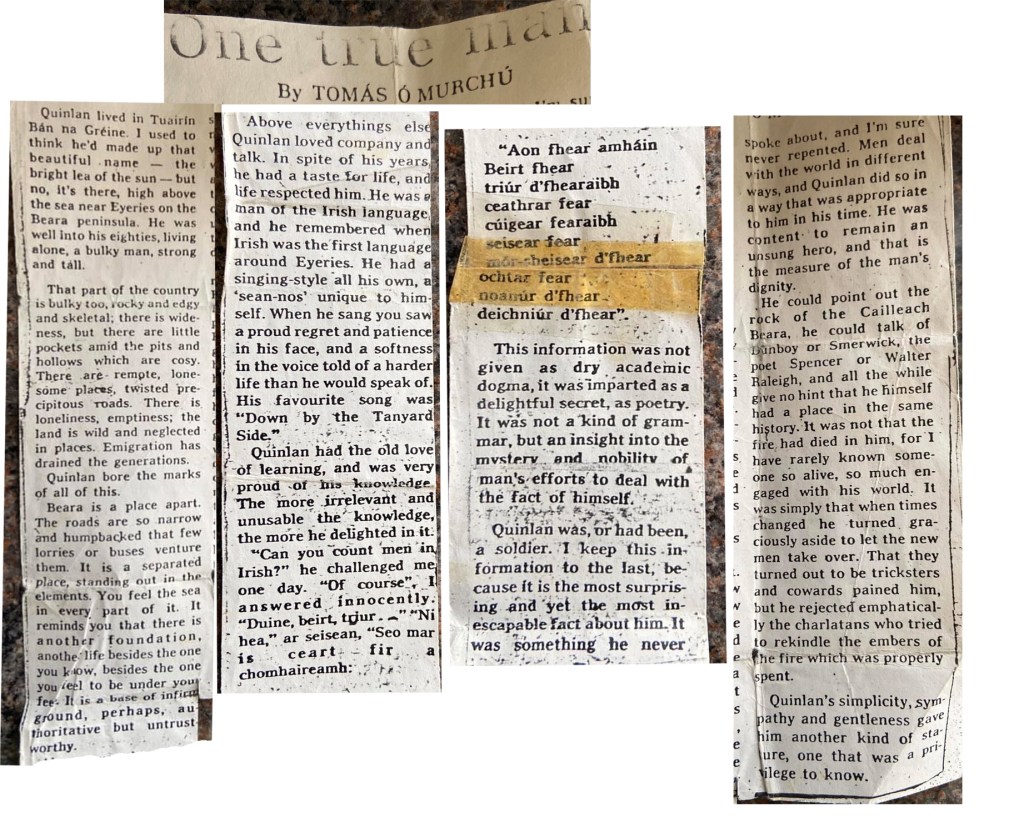

By Tomás Ó Murchú

Quinlan lived in Tuairin Bán ha Gréine. I used to think he’d made up that beautiful name – the bright lea of the sun — but no, it’s there, high above the sea near Eyeries on the Beara peninsula. He was well into his eighties. living alone, a bulky man, strong and tall.

That part of the country is bulky too, rocky and edgy and skeletal; there is wide-ness. but there are little pockets amid the pits and hollows which are cosy.

There are remote, lone-some places. twisted precipitous toads. There is loneliness. emptiness; the land is wild and neglected in places. Emigration has drained the generations.

Quinlan bore the marks of all of this.

Above everything else, Quinlan loved company and talk. In spite of his years, he had a taste for life, and life respected him. He was a man of the Irish language, and he remembered when Irish was the first language around Eyeries. He had a singing-style all his own, a ‘sean-nos’ unique to himself. When he sang you saw a proud regret and patience in his face, and a softness in the voice told of a harder life than he would speak of.

Beara is a place apart. The roads are so narrow and humpbacked that few lorries or buses venture them. It is a separated place, standing out in the elements. You feel the sea in every part of it. It reminds you that there is another foundation, another life besides the one you know, besides the one you feel to be under your fee. It is a base of infirm ground, perhaps authoritative but untrustworthy.

His favourite song was “Down by the Tanyard Side.”

Quinlan had the old love of learning, and was very proud of his knowledge. The more irrelevant and unusable the knowledge, the more he delighted in it: “Can you count men in Irish?” he challenged me one day. “Of course, I answered innocently. “Duine, beirt, triúr …” (One man, two men, three men)

“Ni hea” ar seisean, “Seo mar is ceart fir a chomhaireamh (“No”, he said “This is the right way to count people”)

“Aon fhear amháin, Beirt fhear, triúr d’fhearaibh, ceathrar fear cúigear fearaibh, seisear fear, mór-sheisear d’fhear, ochtar fear, noanúr d’fhear, deichniúr d’fhear” (Similar to the above but in an older grammatical format)

This information was not given as dry academic dogma, it was imparted as a delightful secret, as poetry. It was not a kind of grammar, but an insight into the mystery and nobility of man’s efforts to deal with the fact of himself. Quinlan was, or had been, a soldier. I keep this information to the last, because it is the most surprising and yet the most inescapable fact about him. It was something he never spoke about, and I’m sure never repented. Men deal with the world in different ways, and Quinlan did so in a way that was appropriate to him in his time. He was content to remain an unsung hero, and that is the measure of the man’s dignity. He could point out the rock of the Cailleach Beara. he could talk of Dumboy or Smerwick, the poet Spencer or Walter Raleigh, and all the while give no hint that he himself had a place in the same history. It was not that the fire had died in him, for I have rarely known someone so alive, so much engaged with his world. It was simply that when times changed he turned graciously aside to let the new men take over. That they turned out to be tricksters and cowards pained him, but he rejected emphatically the charlatans who tried to rekindle the embers of the fire which was properly spent. Quinlan’s simplicity, sympathy and gentleness gave him another kind of stature, one that was a privilege to know.

The exact date and publication are unknown but it clearly appeared at the time of Quinlan’s death in 1983

Click on one of the images to see in full-screen